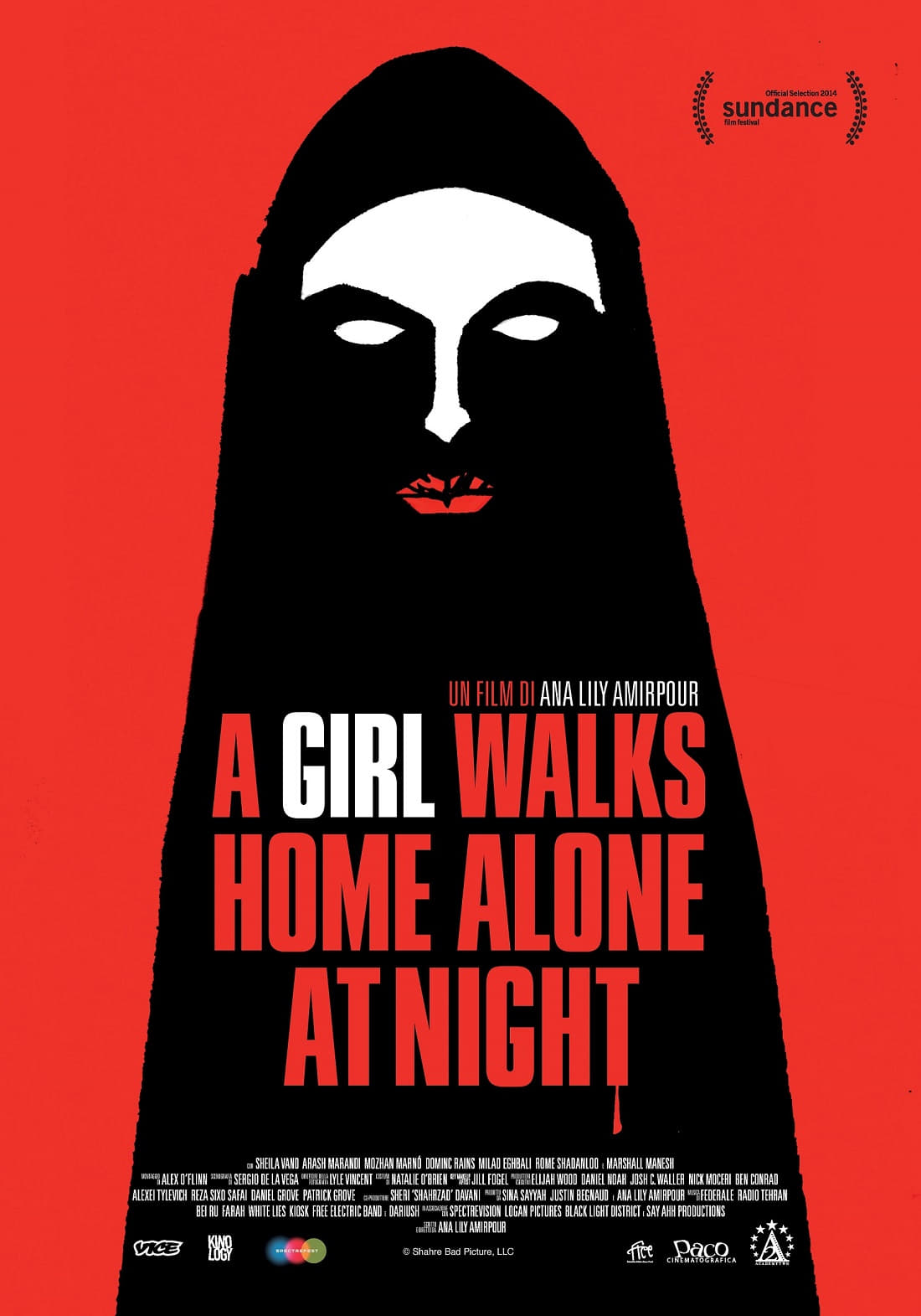

It's the fifth Letterboxd Season Challenge! Theme eight, part two - a foreign horror film!

(Chosen by Jackie!)

(Well alright, A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night is an American production directed by a British-born Iranian-American, featuring Iranian-American actors, with dialogue in Farsi delivered in California locations. It's not any more foreign in the traditional sense than would be any other film by a US citizen embracing their ancestry with others of a similar background. Mistakes made, we press on regardless.)

In A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, director Ana Lily Amirpour has crafted the ideal scene kid movie. Though this is easily construed as a dismissive insult, I mean it as the most earnest compliment I can pay her film. After all, we've a picture whose centerpiece revolves around two characters dressed in all black, both evoking vampiric motifs in their own way, one gently moving towards the other across an expansive widescreen with slowed-down disco ball lights rotating across the wall as the other turns into his embrace, contemplates his neck, and sinks into his arms to listen to his heartbeat instead. All in beautiful black-and-white, all scored to "Death" by White Lies, grinding out across the screen over five whole minutes. There's a weird techno-scored seduction scene that climaxes with a scummy drug-dealer getting his finger chomped off and throat ripped open, a cross-dresser dancing with a balloon, a quiet, awkward ear-piercing scene set against the backdrop of an empty trainyard, and, most importantly, a skateboarding vampire dressed in a black chador and striped long-sleeve. This is a film purpose made to appeal to teens and college students who fuck with Bauhaus and Have a Nice Life and black out their windows to better appreciate the effects of poorly-strung atmospheric lighting on the posters of bands who'll never come to their town but inspire gobs of gif-based appreciation posts and self-insert fanfiction on tumblr dot gov in the year of our lord two-thousand and fourteen. I'm deeply envious towards anyone who saw this right when it came out and felt the full sledgehammer-to-the-chest impact of finally seeing all their predilections thrown onscreen in a glorious act of stylistic exercise - those folks got exactly what they always wanted in their scant two-decades on this dying Earth. All power to 'em, no sarcasm meant whatsoever.

The film lives and dies (and all states between) on how much appeal you can find in a slow-moving mood piece with minimal concessions to narrative. To my mind, it takes the visual celebration pretty damned far, producing numerous memorable moments with little more than its two main characters stood before simple small-town backdrops and allowed to awkwardly interact as Farsi tunes play on the soundtrack. There IS some character work going down, with Arash struggling under the pressure of his father's heroin addiction and eventually dealing himself when their dealer is sucked dry, while the nameless girl displays a streak for enacting justice and intimidation on the people of Bad City, pines for an immaterial long-lost something, and draws closer and closer to Arash through the force of what I (stealing from Connie) can only describe as his big dumbass energy. Act delineations are primarily marked by the girl making a kill that impacts Arash's life in some manner, and their relationship takes a strange turn when she gives him what he always thought he wanted, without the film's taking time to explore what this will mean for them in the future. Beyond these elements, A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night is far, far more about the sublimity of the girl rolling down an empty suburban street with her chador billowing in the wind, or Arash, blasted out of his mind on ecstasy and dressed in a Dracula cape, hobbling to a sitting position while the girl tries to steady him and bring him back to her place. Time beyond these two is mostly dedicated to the small supporting cast, who exist to either more clearly define aspects of the girl's mysterious personality through bracing encounters, or do wrong so she can punctuate the moment with a swift bite to the neck, again through scenes better defined by their stark imagery than writing or acting.

Normally, I'm in favor beyond belief of works that presume the eyeline's slow journey from exposed neck to nestled beating heart are interesting in and of themselves, and turn out absolutely correct. Here, however, I think Amirpour's decision to leave a skeleton narrative at the center results in... not exactly a poorer film, but rather one I can't help see as fallen short of its potential. If it were exclusively a mood piece, following the camera's bliss and leaving interpretation of Arash and the girl's lives entirely to the audience, I'd find the film far more intriguing in a good way. As filmed, there exist components like the girl savagely drinking from an unconscious homeless man, which indicates the presence of a basal need to feed beyond her active, motivated choice in targets, or the unmistakable contrast in how Saeed the dealer seductively dances towards the girl before his death and Arash's careful move to embrace her later on, which raises the question of, "Why him, exactly?" when coupled with the first point. We see the girl express kinship with Atti the prostitute along the dimension of lost dreams and forgotten remembrances, and something in Sheila Vand's performance communicates a bottomless sadness, but there are no guideposts, no indications Amirpour means us to travel these lines of thought with intent or direction. There's a potentially fascinating study about why Arash is the one to bring the girl beyond her situation, or how the girl's interactions with Arash liberate him whilst also crippling what seemed a potential future on his own two feet, or else some treatise on her vampiric nature reflecting or rejecting views of women in Iranian society, whether you choose to construe it as parasitic or liberating, and what that might mean for her as a person.

The film, essentially, has its toes dipped into the pool of conventional narrative just deep enough to intrigue me, and a few moments where it lowers a whole foot in and reveals great potential for these gorgeous images to become so much more in the ripples it creates; yet its dedication to being as much a visually-driven, story-free experience as possible means it never takes the full plunge and explores that which it teases to the fullest. Perhaps I'm being a touch stupid here, asking a deliberately ambiguous film to flesh out what it only means to tease, to elaborate where silence is the intent. In my defense, my own aesthetic concerns almost always lie with purity of form: while a work may eschew storytelling conventions and be for the sake of some ideal towards beauty or horror or coolness, if it chooses to keep a minimal story and even develop this story to some degree, I'm going to want either the story's removal or a greater cohesion between idea and image. Blending the two often leads to feeling a weaker story, and images that would hit more potently entirely on their own or in active cooperation with an idea. Applied here, I understand Amirpour's intent, I really do, but she has tantalized me with the possibility of seeing this picture play out with her thoughts and feelings guiding and interacting with my own, giving me insight into the specifics she's teased. To not get these is consistent with her aims as director, and yet I cannot shake the notion of her film improving if I knew her perspective on some of these more interesting ideas beyond, "It's up to you."

That which is ambiguous about A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night would entice me to think on it as a vagary all the more if it were purely sound and vision instead of neglected narrative, basically. Flipwise, sacrificing some of the ambiguity for specificity would work wonders in my assessment. Again, I'm probably being stupid and unappreciative here, but I like what I like for the reasons I like it, and find it hard to stop thinking this film better if aesthetically pushed further one way or the other. Those scenes that work still work like all hell regardless of my artistic preferences towards storytelling - I've been replaying the "Death" scene in my head all day, it's so powerful a moment. Watch beyond the form-based hang-ups of someone who thinks Danger! Diabolik the ideal comic book movie, and you've nevertheless a splendent post-punk vampiric impression upon the brain, something unique and dark and beautiful, well-worth a watch and however many hours of debate it inspires, internal and external alike. Shred on, you funky little vampire you.

3.5/5