At the start of the year, I claimed comedy films aren't really my thing, that I laugh far more readily at humor divorced from narrative structure or typical stage-bound set-up/punchline stuff, being the kind of dweeb who gets a big kick out've Vinesauce compilations. Perhaps in an example of sticking true to form, or perhaps because I didn't make the best selections for this year's programming, my first round at this comedy challenge turnt out fairly in line with the expectation set by that sentiment. Of everything I kept active tabs on, the comedy challenge scored lowest on average, and led to the most groans and complaints about films simply not being very funny. I wouldn't make TOO much of this, for I'm still plowing ahead on next year's challenge with high hopes, but a year largely dominated by "mn, alright" is a year dominated largely by "mn, alright."

Still, this more muted reaction to the selected films means the ones I DO hold and cherish as my favorites are the ones I truly, earnestly love, and count a few instant favorites amongst their ranks. But since I ran the Cult wrap-up post with the favorites first and the worst second, why don't we flip the script a little here, plow through the negativity right from the breach, savor the positivity for last? Sounds good to me, should sound good to you, let's sally forth:

I Did Not Find These Films Particularly Funny

Coneheads

(SNL Alumni Week)

10: One third weird immigrant origin story, one third new twist on the old SNL sketches, one third budget space adventure, tied together by way too many celebrity cameos, attempts at serious drama, and talk about Conehead sex. Sound atonal and messy? Well, it is. Dan Aykroyd probably should've cashed it in after Coneheads (or preferably beforehand), and stopped before he could further embarrass himself over the last 30 years.

Diplomaniacs

(Wheeler and Woolsey Week)

9: You've not heard of Wheeler and Woolsey? No big surprise, considering Robert Woolsey died in 1938, and Bert Wheeler in 1968, right before the major boom of old comedians reviving their careers on the talk-show circuit. They were a pretty big box office draw in the 30s compared to many acts we now think of as the classics, although Diplomaniacs isn't quite the best showcase of their talent. It's full-up on hokey jokes without strong enough personalities to back them, and the racism... well, there's a lot of it. A whole lotta it. The climax is one big blackface joke lot of it. Eesh.

(Over the last year, nobody has been able to adequately explain why there's a swastika casually sitting in the RKO copyright byline.)

Yankee Doodle in Berlin

(Silent Comedies, Sans Giants Week)

8: Yankee Doodle in Berlin's a touch uncomfortable nowadays. A big, unearned all-American victory dance all over the German's stupid faces fully written, shot, and distributed after the Great War was over, its generally low-energy presentation and slapshod sense of humor is exacerbated by how it reminds one of the way pretty much every Western power convinced themselves punitive, humiliating retribution against the Germanic people could have no possible long-term consequences.You get to see Bothwell Browne's female impersonation act, though, the only time he was filmed performing too, so that's neat.

Ka-Boom

(Queer Comedy Week)

7: Confession: I let Ka-Boom's not being Mysterious Skin get to me more than was probably reasonable. Gregg Araki is not trying for the same effect here as in his earlier devastating masterwork, but while I don't think it fair to damn Ka-Boom on the grounds of not featuring similar themes and performances as a different movie with different goals, I do think it fair to put the film on blast for not featuring much in the way of proper effort at all. The film stinks of a filmmaker diddling round in circles with more a mind for shock and purposeful quirkiness than any coherent point to make, and ends on a note that marks the whole production as pointless in the eyes of those who created it. Fine to not be Mysterious Skin, not so fine to fail at being anything worthwhile yourself.

The Iron Petticoat

(Bob Hope Week)

6: I'm sure there's a Bob Hope film out there for me, one with him putting on an agreeable persona and delivering some jokes I can get behind. When he's in his whole "Boy, fellas, these broads sure are a real pain in the keester, right? Good thing I can set 'em straight!" mode, though, I'm gagging like there's no tomorrow. The laziness extends to the plotting, which dawdles around to such an extent that it loops back round and keeps the jokes from evolving beyond a repetition of one already sour note again and again. Doesn't help in the slightest for the shrew Hope's trying to tame taking the form of one way-too-good-for-this Katharine Hepburn, losing all her usual vocal charm to a really bad Russian accent and the need to act second banana to Hope's buffoon. Maybe the Jerry Lewis collaborations are more my speed...

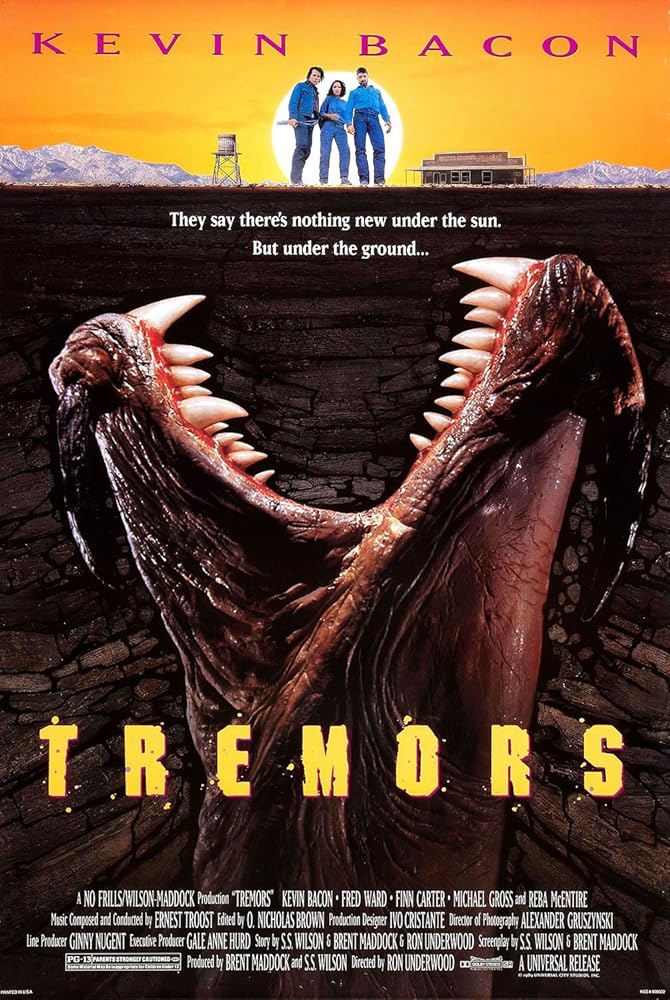

What's New, Pussycat?

(60s Sex Comedy Week)

5: A comedy of errors largely free from errors, what with its contentment to explore characters who're on the same page far more than any whose various hang-ups and quirks clash to produce comedy when forced into close contact. You can feel the spirit of Warren Beatty forcing Woody Allen out've the lead any time Allen's supporting player has a scene to himself and does something funnier than anyone around him. By the time What's New, Pussycat? feels like waking up and actually doing something amusing, it has spent so much time on blah material, I just don't feel like going along with it, which is a poisonous attitude for a comedy to install in an audience member during its zaniest moments.

Boy, Did I Get A Wrong Number!

(Female Comedian Week)

4: God, why did I schedule myself for two Bob Hope films in a row? Why'd I have to make one of them Boy, Did I Get A Wrong Number!, a sex comedy free from any sex that treats its most risque player like an agency-free prop for Hope to toss about like a sack of potatoes? Why'd it have to be so square and bland, sandwiched right between the wilder excesses of true 60s counterculture and the more fully-fleshed beats of 70s television programs in the same style? Why, when presented with any notable female comedian as the subject for this theme, did I go with a Phyllis Diller production where she's barely in it, and not able to take advantage of her greatest strengths besides?

More like Boy, Did I Pick the Wrong Film. You may shoot me now.

Mother Riley Meets the Vampire

(Long-Running Series Week)

3: I listened to some've Arthur Lucan's Old Mother Riley comedy records from the 40s before watching this, the ones he made while his wife and long time comedic partner Kitty McShane played foil to his doddering-whipcrack old woman character. Although the act WAS stronger in its intended form than with Lucan trying to carry on solo, I doubt McShane's presence would've saved a film produced at the tail-end of 16 years' constant production with a completely dry well for creativity and budget alike. Lugosi's about the only fun element in Mother Riley Meets the Vampire, and he's simply not around long enough for you to do much more than smirk at his usual over-the-top silliness inherent to his poverty-era performances.

Billy Madison

(Comedian You Hate Week)

2: Oh, like there was any hope for Billy Madison with this theme. I won't skewer Adam Sandler quite so deeply as I might otherwise, given Uncut Gems is doing the round and inspiring a whole slew've career reappraisals, but I see no reason to claim his early mainstream successes point to anything other than a man who knows and appreciates anything beyond the lowest level of filth. This is a vile, hateful, miserable little film, not even well-made by the standards of a 90s gross-out slobs vs snobs comedy, and it makes me want to puke thinking about it again. That phone call scene with Steve Buscemi is one I've seen multiple times in tumblr gifs and videos, and I thought it genuinely hilarious, so learning it has just a tiny little bit extra at the end where it turns into a borderline transphobic gag just makes me all the angrier at Billy Madison for ruining something I actually liked.

The Pick-Up Artist

(80s Teen Comedy Week)

1: Would The Pick-Up Artist be a better movie if Robert Downey Jr weren't playing the worst person in the whole wide world as the film tries to pretend he's secretly a really nice guy who should be seen as everyone's friend? Yes, but then it wouldn't be The Pick-Up Artist. Fun fact: director James Toback is apparently this sort've harassing, abusive scumbag in real life, so there's absolutely no reason to look on his work as anything other than a celebration of how degradation, misplaced charm, and engineering hostile or dangerous situations are the ideal ways to catch a mate! Also I don't think it's very funny, and Molly Ringwald doesn't have anything she brought to The Breakfast Club here.

The Dishonorable Mention

(Stoner Comedy Week)

I very purposefully did not grant Pineapple Express a rating, because I acknowledge my inherent, extreme distaste for stoner culture put me in a position to hate it before I ever gave it a chance, and kept me from enjoying what I do believe is a fairly well-structured movie with some good jokes in its pocket. However, this lack of rating does not prevent me from putting it on record that I still kinda just hate its stupid guts, nor from posting the "IT'S NOT FUCKING WEED YOU PIECE OF SHIT STONER" image again in lieu of thinking about it further.

Enough negativity, let's talk funny!

I Laughed At These :D

(Dramatic Actors Going Funny Week)

10: I don't remember which actor I singled out as the one making a notable rare comedic turn when I picked this, considering they've all done comedy and drama with fair frequency, but I'm glad I chose Burn After Reading for a watch anyways. John Malkovich's rage against everyone asshole, George Clooney's Smoothest Man in the World slowly degrading into total paranoia, Brad Pitt's stunning turn as a man with as few brains as he has audience-grabbing charm (I seriously don't understand why my dad hates this guy, he's great in everything I watch), Frances McDormand's cottonmouthed flailing for competency, they're all wonderful pieces of a story that gets bloody and senseless before anyone figures out what the hell is going on anyhow. Special props to the dildo chair and everything with JK Simmons.

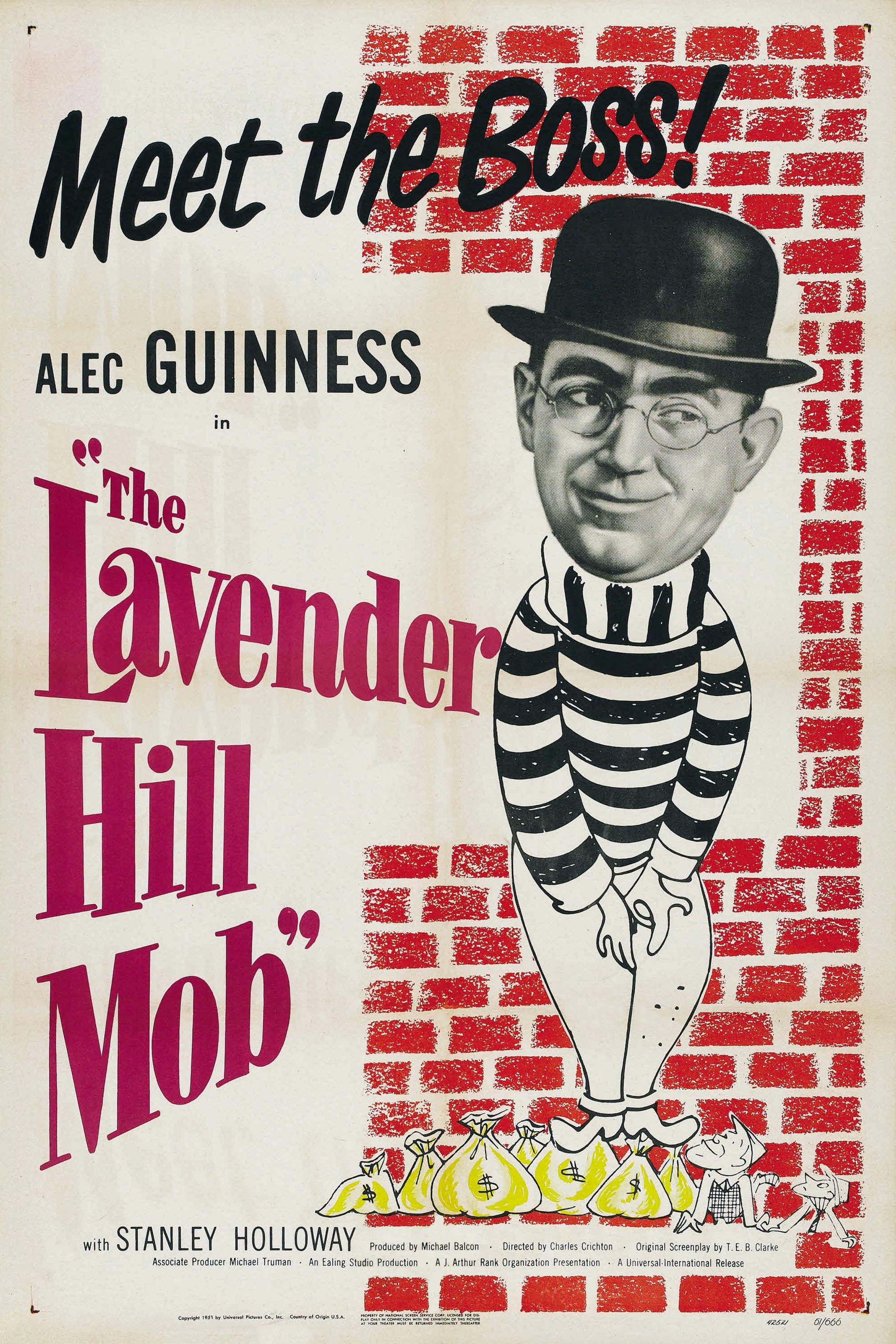

(Ealing Studios Week)

9: As I mention in my review, I didn't think The Lavender Hill Mob an especially special film immediately after its last frame, not compared to the same year's The Man in the White Suit. Further consideration found me appreciating the way it exploits the camaraderie between its characters and a new ridiculous situation every scene to set off a series of firecrackers that SHOULD cause the whole thing to explode with manic energy, yet remains hilariously tamped down because we mustn't let ourselves get TOO ruffled, you know. Great acting and clever filmmaking combine for a solid tale of comedic woe. I'm still of the opinion this is one of the few times American censorship standards of the day forced the ending to be even better to release across the pond.

(Katharine Hepburn Week)

8: Love me some Howard Hawks. Love the euphoric madness he brought to every picture, the unique, undeniable sense of a man happy to run rabbit rampant across the silver screen in the name of a laugh, in whatever form he liked. Bringing Up Baby contains the single funniest moment from this entire challenge, for while I'm still a tad iffy about how Katharine Hepburn's character was written, it all becomes worth it when she storms back into the picture with a wild leopard in tow, completely oblivious to the danger she's in, as a final match in an already flaming powder keg. Plus, y'know, she's tag-teaming with Cary Grant in one hell of an upper performance, and making ol' Bob Hope look hopelessly flacid about 20 years before he had the chance to do the same himself.

(The general consensus is right: "Because I just went GAY all of a sudden!" really is a hilarious line in an already funny scene.)

(Japanese Comedy Week)

7: Things fall apart in The Crazy Family. Each member of the Kobayashi household has their little quirks, same as any family, which grow ever-more pronounced as the stress and isolation of the suburbs coupled with the absurd standards of Japanese family life push them deeper into their eccentricities. When Gakuryuu Ishii touches a live wire to their wavering sense of sanity, the whole film erupts into a crazy battle between outrageous personalities, with our central father figure growing nihilistically homicidal. Nobody's stable, everyone thinks they're the only sane person left despite all appearances, and they're all out for blood as they literally tear their house to shreds. It's hilarious, and I'm gonna bluntly tell you that you should watch it, considering you've probably not heard of it compared to all the other top 10 selections.

(Any Comedy You Like Week)

6: A pleasant last-second surprise from the very last comedy film choice of the year! I've rambled about how Hitchcockian Smokey and the Bandit is in my review, so allow me to simply say its high-speed yet easy-going spirit, with Sally Field settling into Burt Reynolds' rhythm of life just as easily as Jackie Gleason lets it outrage and fluster and ruin his day, a murderer's row of colorful CB-usin' truck drivers on tap, and the musical styling of Jerry Reed permeating the whole film makes a wonderfully engaging time. You've gotta love any film that treats expensive top-of-the-line vehicles like big kid toys to be thrown tumbling all throughout the American South.

(AFI Top 100 Comedies Week)

5: To reuse an analogy from the review: Two men playing poker and blatantly cheating on every hand, only to lose to a woman who sat down and played the game straight despite being a little hazy on the rules. With those men being Tony Curtis and Jack Lemon, the woman being Marilyn Monroe, and the whole thing being orchestrated by Billy Wilder with a focus on executing such a dynamic again and again and again with new ideas and smartly-written dialogue on every reset, it's no wonder Some Like It Hot ranked so highly amongst the American Film Institute's voters, and there's no trouble understanding why it's still widely beloved today. Way, WAY better at crossdressing gags than pretty much anything I've ever seen. Also, Joe E. Brown as Osgood is just plain perfect.

(Marx Brothers Week)

4: The first film I found actually, no qualifications hilarious this challenge, and one I continue to have trouble articulating why. Even accounting for how the Marxes lost their long-time producers after a studio change and dropped Zeppo for A Night at the Opera, the hell raised by Groucho, Chico, and Harpo on their journey across the Atlantic is so howlingly funny yet honestly sweet and wholesome that I can't imagine the kind of person who wouldn't find them funny. We all remember the contract scene, the stateroom, Harpo's piano playing, etc, but I'm personally more inclined to name the Marxes gradually emptying a bedroom of its beds in a circular chase with a delightfully pompous police officer. Funny's funny, the Marxes were funny, and this movie's a hoot.

(Steve Martin Week)

3: Expecting Planes, Trains, and Automobiles to be indiscriminately meanspirited and cold-hearted towards the world entire, and finding it actually a wryly self-aware, even-handed, ultimately positively sentimental work is downright one of the best surprises I experienced this year. After years of keeping John Candy off my radar for no real reason other than general ignorance, I now regret not giving him a chance sooner, as he's a total delight to watch, and stunningly easy to care for without losing his loudmouthed, annoying traits. Steve Martin, for all his badgering and rudeness and self-satisfaction, gets it way more often than he's capable of giving, and learns to love and accept this boorish man he thought he could only hate in a sequence that had me begging him to do the right thing through my TV screen. Probably the perfect holiday travel comedy? Yeah, I can get down with that descriptor.

(Screwball Week)

2: The film that clarified Howard Hawks for me. Prior to this, I couldn't put my finger on what made his work so damned special in my eyes, what common element united the man noted for experimenting in every genre available. The above-described sense of mad euphoria is plain as day in Ball of Fire, a rip-roarer of a comedy if there ever was one, with too many endearing bits and bobs to mention. The best strategy I can think of is reminding everyone of how Hawks often cited an approach centered around "Three good scenes, no bad ones," and suggesting that if the matchstick rendition of Drum Boogie, the conga lesson scene, and Gary Cooper confessing his love to Barbara Stanwyck in a darkened bungalow are merely good, then the concept of "great" has been rocketed far beyond any mortal's reach. Not only my second favorite of the year, my absolute favorite of the six Hawks productions I've seen, and likely to remain so for a long time.

(Massive Ensemble Week)

1: Are there words? A large portion of my review for It's A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World consists of me alternately listing out my favorite parts in a massive block paragraph and exploring how it flows structurally for a few more, but are they words enough? Can anything explain the sheer joy of watching Stanley Kramer exercise every comedy star under the sun in a madcap race to the prize for nearly three hours, short of watching for yourself and seeing with your own eyes? I'd like to think one can do so, for one should be able to communicate just about anything with the right words and sufficient length... but hell if I know what those words are or could be. It's A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World moves with a fleetness a film its size reasonably shouldn't, contains more funny moments by proportion and volume than anything else I watched this year, and has a killer structure to beat all with Spencer Tracey as the unexpected MVP. It's a screamer to end all screamers, the kind of project that could only happen once and then never again, and they pulled it off beautifully. The lone five-star film of the bunch, and it deserves it like no other.

Honorable salutes to the special effects wizardly and theme music of Killer Klowns From Outer Space, Cantinflas' Spanish wordplay that I couldn't understand thanks to shitty subtitling in Romeo y Julieta, the Birmingham Jail sequence from Stir Crazy, and Sean Penn's little smile from Fast Times at Ridgemont High, proudly pictured above.

See y'all in 2020 for even more comedy stylings, hopefully ones better on average than this year's!