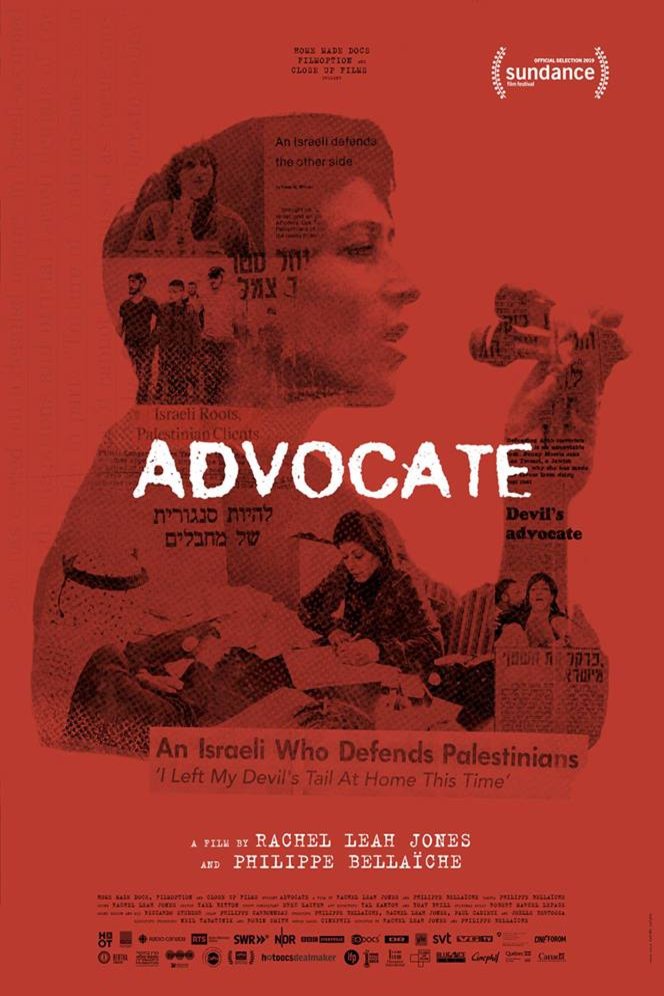

(Skipping Saturday's screenings kinda sucks on my end, because the presenter announced the judges' having chosen Advocate for the CICAE award right before the screening, and while I'm going to give it a glowing review, finding this out before giving the film a shake for myself feels like it has ever so slightly biased me against it in favor of thinking Aga the better picture. We'll try and leave that matter for the wrap-up post on Thursday, though, and simply write about the film as seen.)

The greatest trick Rachel Leah Jones and Philippe Bellaiche pull in Advocate is purposefully withholding a critical piece of information until the last moment. They have, of course, an admirably clever bag of tricks to draw upon throughout, and in deference to the effectiveness of this trick, I shall do the same until towards the end, focusing instead on their other techniques for the time. Needless to say, all the tricks in the world cannot do squat without a strong subject, and Lea Tsemel is quite worthy of nearly two hours about her life. The film is divided between her latest cases defending a thirteen-year old Palestinian boy who stabbed two Israeli teenagers and a young Palestinian woman who detonated a bomb that killed nobody but left her mangled, and regaling her life story as a lawyer and human rights activist through media pieces throughout the decades and interviews with her family and clients, who are often one and the same. In the present day, we see her researching cases, engaging in rapport with her legal team, dealing with press outside the courtroom, counseling her clients, and living her life in the between-spaces, giving the impression of a tough, spirited professional who still embodies great compassion without needing to set a second of it during trials. In the past, we are perpetually reminded of how the uneasy and violent Israeli occupation of Palestine has manifested itself in small ways over the years, and understand the importance of even one figure looking behind the decrees of terrorism and inhumanity to try and help those others decry as despicable.

In both modes of documentation, the screen often splits, typically directly along the horizontal middle, showing two different angles on the same event from either vertical slice, or segregating a third of live action footage on the left or right from photographic montages in the remaining two-thirds. It's a simple technique, one used to increase the density of parsable information in thousands of documentaries, but it has greater impact for what often happens when part of the frame contains Tsemel's clients. To protect their identities in moments where their faces appear, the filmmakers have commissioned traced-over animations of the live-action footage, rendering a large part of the screen a crinkled mass of paper with inked impressions of people moving through its frame. Crucially, the paper is not mere drawing paper; it is comprised of rapidly shifting legal documents, court records and written arguments and printed laws, the sort of things Tsemel frequently consults in her line of work. When the line dividing the client from the solid, present reality takes the same form as the line dividing footage from the past and an interviewee from the present, an entanglement forms.

These clients, though hopeless cases nobody would consider worth defending at first glance, are not just defendants in a trial with the whole nation of Israel set against them. They are decidedly intertwined with all the lost causes and hopeless cases Tsemel has championed in the past, their fates resting on precedents formed by their attorney and the few like her who think them worth the effort. Success doesn't just mean freedom or a reduced sentence, it means another stack of papers in the file, joining thousands of others who might help future Palestinian freedom fighters. Even failure means another well-documented example of injustice, of how the state and the people it represents refuse to hear any possible qualifying evidence or extenuating circumstances, a tiny step forward but a step all the same. The people Tsemel represents walk through her case histories because they themselves have become part of those histories, for good or ill, and there is perhaps no better way to defend their identities than by constantly reminding the audience of what they will represent legally in decades to come.

And yet, the last time we see Ahmed, the thirteen-year old who stabbed two Jewish boys and plead no intent to kill, the well-worn collage of documents fades away, as does much of the detail, and we only see a young boy's face, rendered with simple black lines against stark white before the slide of an invisible elevator wipes it away. For they lost the case - Ahmed was tried as an adult and sentenced to a full twelve years. Leah Tsemel has lost practically all of her cases. The numerous landmark trials we're introduced to throughout the segments documenting her own history, including the time she defended her own husband for distributing anti-Israeli literature, all ended in failure. She has lost time and again, counting her victories in the years she has shaved from her clients' sentences, the legal precedents she has set so she can do better next time, the tiniest little things others might only accept as consolation prizes. It's the only way she can get through it all, and even still, after nearly fifty years' hard work as her state's greatest devil's advocate, she still needs a significant amount of time to process the judge's final ruling that ignored her every argument in favor of reinforcing first impressions. After all, a young man has to face the realities ahead of him all alone, and a young woman's family feels no recourse when their suicidal daughter and sister is branded a radical terrorist. And we have to sit there with her, and watch it all play out, and feel it with her from a million miles away.

Advocate does not pretend there is any hope a lone defense lawyer can resolve the Israel/Palestine conflict, or turn the tide of public opinion, or even make the courts care about justice when a Palestinian stands as defendant for a violent crime. But it does offer us a picture of someone who knows all of this is impossible, and finds reason to continue the fight and scrape away at the problem while protecting and advocating for those who have no one else, while still remaining vibrantly, personably human through it all. Letting us know Lea Tsemel has stood at the intersection of all these historic cases, inspired so many in her life, fought for decades upon decades simply because she cannot look into suffering eyes and think their plight right, and conveniently forgetting to mention she has only a small pile of relative victories to show for it rather than a blazing record of unqualified wins until the very end forces us to consider those mildly lighter sentences and changes in convicting language as valuable and important as she does. No matter the ongoing injustice of occupation, what she has done matters. It has to if any of this is to come to, if not a peaceful end, then a less horrid state.

4.5/5

***

Throughout the last week, I've had a particular picture of Roger Ross Williams' Travelling While Black VR experience in my head. One hears about an Oculus-enabled piece that takes one through the history and legacy of the discrimination and violence African-Americans experienced on the road throughout the 20th century, one imagines being placed into black shoes to experience such discrimination and violence firsthand. Facing the reality of what happened firsthand, from the inside, and considering the emotionally straining impact being targeted while minding your own business takes. On reflection, such an experience would most certainly become exploitative and needlessly salacious, but I could imagine no other form the film would take, and so stuck to the assumption until I actually sat down and strapped on the headset inside the restored Old Pueblo trolley bus. And boy am I glad that Ross Williams found a far more creative application for the VR tech, because it communicates its ideas far better than what I pictured.

See, the vast majority of your time in the virtual space of Travelling While Black is spent sitting inside Ben's Chili Bowl, a Washington DC diner named as one of the safe havens for black travelers in The Negro Motorist Green Book. Though your location within the diner will shift behind fades to black, and occasionally you will find yourself creeping through the back room in the haze of midnight or watching what seems to be the thick smoke of an evening riot while voice-over plays, the point is less transportation to a different time and place, but rather a grounding in the immediate now. Your viewpoint is that of an observer in the booth while the people next to you recount their stories of life on the road in the mid-20th century, their fears of being killed on a police stop just for being black, the relief they felt whenever they stepped into a space named in the Green Book. There's brief visual aids in the form of footage playing on the ceiling during some of Sandra Butler-Turesdale's narration, and a moment when you can look to your left during Courtland Cox's segment and see him as a young man reflected in a bus' mirror while the normal diner scene plays to the right, but for the most part? You are there in the diner, listening as if you were there in the booth with these people, listening to their stories like it's any other day.

The effect is, for someone like me who's never done VR before, perhaps a little too convincing. Even though I'm pretty sure my headset was fuzzy and out of focus, there were times in my glancing around to take in details that I would lean forward or to the side because I wanted to get a better view of something which caught my eye, only to be reminded the camera was in a static position and would not respond to THOSE kinds of head movements. Same thing goes for trying to rest my hands on a table that wasn't there so I could listen more comfortably. On the flip-side of this token, though, the extended segment with Samaria Rice discussing how her son was murdered whilst traveling in 2014 hits particularly hard, because it is difficult to think of yourself as anywhere but in the booth with her, and despite the ability to look anywhere else in the restaurant, I find myself compelled to look her square in the eye as she described every detail of the night. Perhaps her testimonial was raw and powerful enough to do this in a more conventional filmic experience, but the grounding offered by VR makes it an even more impactful part of the experience than those brief segments that matched my expectations.

Travelling While Black cuts to the heart of the matter, and makes it clear that listening to black voices coming from black spaces and black experiences is more important than vicariously living those experiences in a facsimile of the real thing. It is not the kind of experience I can rightly rate, for its impact lies beyond the conventions of how I typically judge a work, but I can easily tell you, it is more than worth the time if it comes to your town, or is made available for commercial purchase through Oculus. I'm even willing to overlook the headache that kicked in halfway through the drive home and persisted for hours afterwards if it meant a chance to sit and listen and feel in this manner.

No comments:

Post a Comment