(Chosen by me!)

There's some debate to be had over whether traditionally-defined progenitor of the documentary film, Nanook of the North, fully deserves the title. After all, director Robert J Flaherty did not strive to capture the Inuit people as they lived at the time of production, but rather hired several actors of Inuit descent to play out the customs of their past like they constituted the entirety of Inuit culture. Realities were ignored, narratives invented, details blurred, and overall the production is thought of as presenting a false impression of what "Eskimo" life was really like, based on American cultural assumptions of the day. One does not come here to bury Flaherty and his entire historic footprint, though, regardless of how backwards his views and methods were, to the point of falsifying his star's name and cause of death two years after release to make his work seem more "authentic." Much as Nanook of the North lacks true authenticity, one can still find the shape of things to come over the next century in its restagings - many of the practices on-screen were real Inuit traditions and skillsets, and in retrospect there's a certain truth to the falsehoods, if one useful for documenting the director's biases rather than the lives of those in frame. It's far more docufiction than pure documentary, and its usefulness has shifted radically with the times, but a documentary it is all the same.

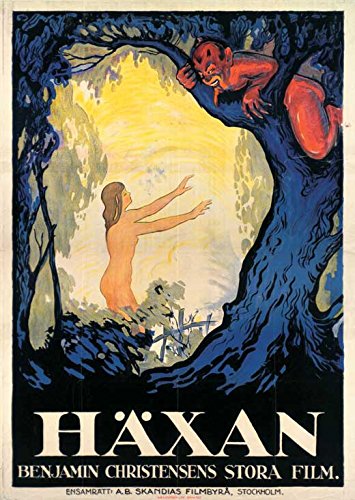

We encounter a similar issue of classification when discussing Benjamin Christensen's 1922 experiment, Häxan, retroactively subtitled Witchcraft Through the Ages for a 1968 American release. On first blush, it seems very much in what we'd call the documentary mold, though perhaps closer to recorded lecture than anything traditionally filmic, what with the ongoing discussion of sources to be found in your playbill and the presence of a pointer guiding the eye through woodcarvings and mechanical depictions of hell. The tone is academic, the focus on understanding how medieval scholars and priests understood the world to function. Even when the camera shifts to presenting a filmed scene of a witch's hut in centuries past, the setting seems plausible, and the witch more an old, knowledgeable woman trusted by her younger fellows in the village as a source for miracle remedies with appropriately magical-sounding ingredients. Shortly after this, however, Christensen's intertitle narration asserts that belief in the devil reached such heights as to make Satan a physical reality, and he pops up as Lucifer himself from behind a monk's bookstand. We're off to the races, and won't make contact with more sensible reality for a good hour.

If Christensen's film veered into the fantastical and never returned, I'd feel no qualms about its classification. The introduction is academic and informative, yes, but once you start watching witches fly through the night and kiss the devil's ass and eat stews of toads and unchristened children with the same eye of scholarly interest, you're more than likely exploiting safety and comfort communicated by the opening tone to scare the audience. Let's all watch as Satan brings his faithful to a palace in the sky of wealth and delights they can never touch, tempts young maidens to wander nude through the night air from their window, and drive a convent of nuns to madness with the merest hint of his presence. It's all realized with sets and costumes reminiscent of 15th century woodcarvings and manuscript doodles, and it's transgressive as hell for the time of release. Just hunker on down for a bit of witchcraft-based horrors from the best a Swedish film studio's money could buy in the early 1920s. Should be keen, yeah?

The issue becomes muddied when we consider how Häxan ends. We return to reality for a brief consideration of torture devices and how we as a modern audience might react if forced to endure their infernal pains, dive back in for the aforementioned mad nuns passage, and then catch our heads for a final segment interrogating possible explanations for witchcraft in the past. To Christensen's mind, much of the abnormal behavior cited as proof of allegiance to Satan can be explained as symptoms of hysteria in its various forms (or somatic symptom disorder, in the more up-to-date scientific vernacular). Coupled with prejudiced and fearful attitudes towards anyone deemed a social outsider, or too temptuous to the faithful, or just plain not liked by a strong authority figure, a mental disorder could handily explain the vast majority of witch trials conducted by inquisitions across Europe over the centuries. Witches, Christensen asserts, were never real, yet despite advancements in medical understanding of the mind and greater societal tolerance towards those with potentially frightening differences, the attitudes which fueled a fear of witches persist today. After all, only the wealthy are afforded the full care of a fully-staffed clinic - the poor must endure and suffer in over-packed madhouses, and when you get down to it, what is forced, indefinite incarceration in an asylum but a more drawn-out form of burning at the stake?

Strong argument. Resonant mindset. Surprisingly comprehensive call for tolerance from something made nearly a whole century ago. Applicable to discussions about how to handle mental illness in the modern day. Damned strange case to make after indulging in images that treat witchcraft as real and immediate and vicarious as anything else in the picture.

It is here we encounter a difficulty in classifying Häxan, for it is possessed of a dual mindset. In the one, witchcraft is as fake and ludicrous a notion as Earth at the center of a cosmos presided over by a physically tangible God, and has no place in modern times save as a specter of ills past; in the other, witchcraft is decidedly more solid and effective a cinematic reality than the unmoving images from manuscripts centuries old, and the very director calling magic and the supernatural a sham is free to run about in full devil costume, churning his butter and waggling his tongue into the camera all the way. Christensen never acknowledges the disparity, casually showing an old woman driven to false confession by continued torture before presenting her wild inventions in a manner that suggests genuine vicarity. From the way the film moves across subject to subject, witchcraft's existence only really depends on the needs of the moment. The film is open to presenting beliefs born of ignorance and prejudice as just that, or presenting them like Flaherty would his Inuit subjects hunting with handheld harpoons, as the only conceivable reality. There exists contradiction between these two modes, and it would seem to strain even the definition of docufiction to include Häxan amongst its ranks.

To solve this, I suggest we consider the film's roughly middle portion, the only passage to last across more than one of its seven segmented Parts. The depiction of a witch trial from initial accusation to death of the last far-flung victim is as much fiction merely informed by historical research as anything else in the film, and its characters more indebted to the traditions of theatrical melodrama than a modern understanding of historical reenactment (or at least good historical reenactment - looking your way A&E), but it also makes the strongest argument for treating Häxan as a documentary of its own sort. Amidst scenes chronicling false confessions as if they were undeniable truths, we find the inquisitors engaged in psychological torment of their charges better suited to chilling the blood than any naked moonlit dance or newborn sacrifice, or even the suggestions of instruments at torture in later sections. They play false friend to trick a woman into confessing she may have heard of how to perform one tiny, inconsequential piece of magic at some point in her life; they drag a woman's family before her to guilt her over how they'll suffer when she's gone; they find inconsistencies in the stories as told and feel a tiny pang of empathy for those they torment, and go to their leader for an explanation of how this is REALLY the result of some magic spell or bewitchment upon their hearts. We find, in short, the true monsters of the movie, the men who must hold directly contradictory views in their minds to assuage their guilt and carry out the destruction of several entire families to burn out witches they know probably do not exist, and yet must exist, because why else are they bringing about such suffering in the name of God?

Consider again how Christensen asserts these attitudes persist to the modern day. We, like the priests and scholars of 15th century Europe, consider ourselves learned, better informed about the mysteries of the universe and the depths of the human mind than any before our time. And like the priests, he posits our advancements do not preclude cruelty towards the disadvantaged, the oppressed, and the othered. In order for this to be so, a similar form of doublethink must occur in our time, be it willful ignorance of the world's sufferings, or a distant self-justification that those who suffer in such a manner must deserve it in some way, or a personal self-justification of our own righteousness when we engage in such. Per Christensen, a belief in witchcraft and the devil must persist to the present, in its own insidious way. No longer in the literalized form of thinking suspicious persons as literally in league with the devil (for most of us), but in attitudes that say we are enlightened to the ways of the world and the plight of our fellows, yet allows them to burn by no fault of their own all the same. This film is, in effect, a documentary of a mindset.

For Christensen's film to reflect this doublethink in its construction is, I should think, for Christensen to acknowledge his own shortcomings as an academic and documentarian addressing this issue. On one level, to discuss witchcraft and the inquisitions directed at witches, one must treat the fantastical and real as matters of equal interest, particularly in a visual medium like film, where simply saying "This is what they believed witches did" is not the most effective means of communicating the idea. On another, talking about the intellectual and moral inferiority of persons past invites one to derision by future viewers and critics, as Christensen's use of the medical term hysteria does in a time when said word has passed into common vernacular as a derogatory phrase. Playing into the necessarily contradictory views in this manner insulates Häxan to an extent, ensures its ideas can remain evergreen. After all, my notions about what constitutes a progressive, informed viewpoint will one day too seem hopelessly ignorant and backwards. There are doubtlessly areas in my life where I turn a blind eye to suffering and justify it as necessary and right, as there are for all. I, too, believe in witches after a fashion - it's just the way these things go.

We'd all do well to try and remove the bewitching of our own doing, treat those in our own lives better, and call for our governments to do the same, especially where the mentally ill are concerned.

4.5/5

No comments:

Post a Comment